| 00:00 |

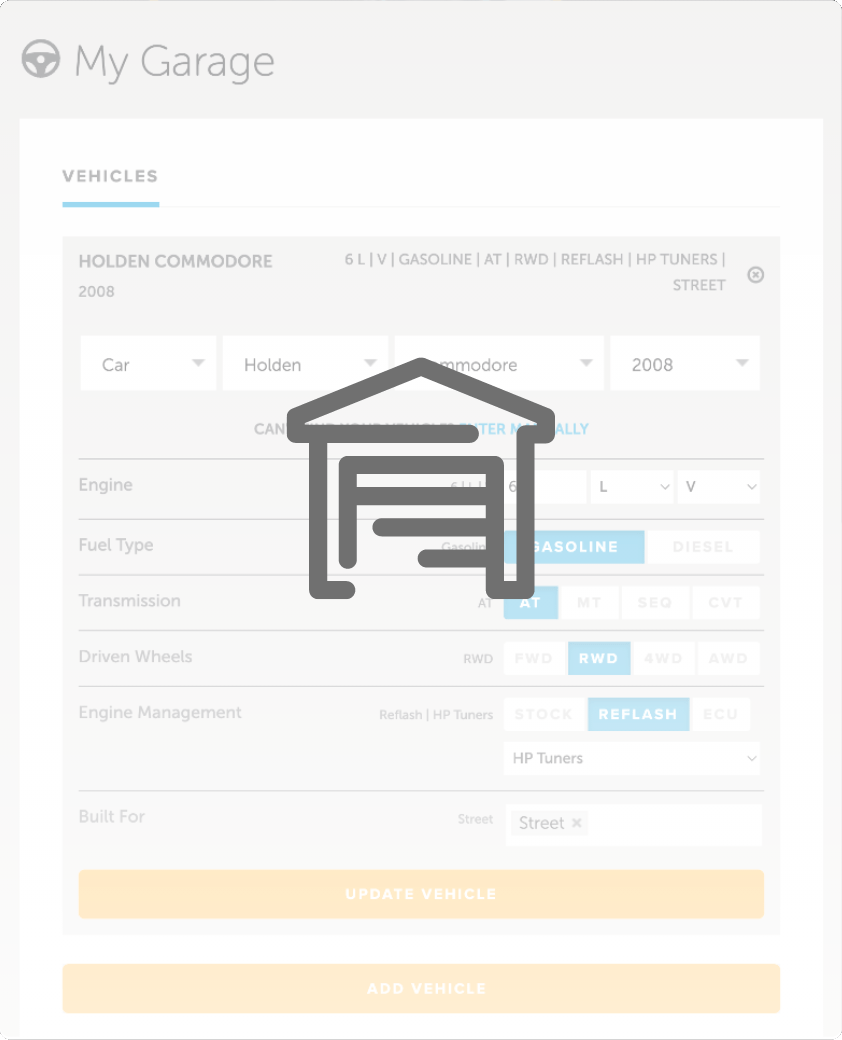

- We now have a model of our valve cover and the visual aid has already gone a long way in terms of analysis, showing us how our design will fit and function.

|

| 00:09 |

This analysis process really goes hand in hand with the CAD modelling phase as we tend to analyse and make changes to the model as we go.

|

| 00:18 |

If the part will function or not is fairly obvious with our valve cover since it really just needs to fit and seal against the flange surface.

|

| 00:27 |

But we also need to think about any issues that could be found during manufacturing and when using the part like machining limitations around accessibility or tool sizing.

|

| 00:37 |

The first and most basic thing we can do is check the dimensions of our geometry using our measure tool under the inspect tab.

|

| 00:45 |

With this, we can measure the critical dimensions we're interested in and compare these to our physical measurements from earlier.

|

| 00:52 |

Ensuring our physical material is correct, we can also check our mass properties to see how much our part will weigh.

|

| 01:00 |

For this part, it's not overly critical as long as the weight isn't excessive.

|

| 01:05 |

Sitting at around 4.7 kg, this isn't what I'd call light for a part like this but it's not going to get significantly lighter without reducing the strength and that's not something I'm prepared to risk.

|

| 01:18 |

This really goes hand in hand with stress analysis or the use of FEA which we could use to determine the response of the model to simulated real life stresses like structural loads, fluid pressure or thermal stresses.

|

| 01:32 |

This part should be under structural loads given that the work we've done to align the mounting holes is correct and the fixtures don't stress the part from misalignment.

|

| 01:41 |

It's also safe to say the crank case pressure inside should not be an issue for 5mm thick aluminium, especially as the engine is dry sumped which helps to lower this pressure.

|

| 01:52 |

There will be some thermal stresses as the part heats and cools and vibrations can lead to fatigue if the part is stressed but this part should be over engineered with plenty of thickness and filleted corners to reduce stress concentrations.

|

| 02:06 |

Also, as the part is to be made from billet, it should be relatively free of residual stresses from manufacturing processes, at least compared to cast, welded or a formed part anyway.

|

| 02:19 |

With all this said, it's just not worth the time and the cost in the case of Fusion 360 to complete FEA on this part but there are some tools we can use to better understand the strength of our parts such as the design advice function under the plastics tool set.

|

| 02:35 |

Although the intended material for this part is aluminium and not plastic, this will allow us to understand the minimum thickness to check for any potential weak areas.

|

| 02:46 |

Unfortunately this tool is an extension, meaning it costs extra to use but simply using the section analysis and measurement tool, we can complete this same analysis ourself, naturally though it's going to be a lot more time consuming.

|

| 03:00 |

While our design is complete, we still need to consider design for manufacturing or DFM.

|

| 03:06 |

The first thing we should consider is tolerances to make sure our manufactured part will fit in the mounting location.

|

| 03:14 |

As our part is to be made in a quality CNC mill which will be plenty capable enough of achieving suitable tolerances, this isn't much of a concern.

|

| 03:23 |

However, we will still note the required tolerances on our technical drawing.

|

| 03:28 |

The next thing to think about is the limitations of our manufacturing process and in this case, this is best covered with the manufacturer or machinist themself.

|

| 03:38 |

For this project, once I was happy with the model of the valve cover, I exported a STEP file simply using the export function under the file tab and sent this to the machinist.

|

| 03:49 |

Specifically Bruce of Five13 Fab here in New Zealand.

|

| 03:53 |

Bruce reviewed the design and we discussed the requirements for the finished product.

|

| 03:57 |

He expressed his plans for machining the part to provide the best results and a quality finish and suggested some changes to make to the model to help.

|

| 04:06 |

This may seem trivial but it's actually one of the most important stages of the entire project.

|

| 04:12 |

It's critical to have good communication with the manufacturer to ensure that we get what we need, especially for such an expensive part.

|

| 04:20 |

While the original design could have been machined, there were some changes required for the best results.

|

| 04:26 |

The original design was 70mm high which is the dimension of a common billet size that was available.

|

| 04:32 |

Unfortunately though, this wouldn't allow the top and bottom of the part to be machined.

|

| 04:37 |

Rather than stepping up to the next billet size, the model height could be reduced to 69mm, leaving half a mm on each side which is enough for finishing machining passes.

|

| 04:49 |

The wall thickness wouldn't need to be reduced for this, just the clearance over the top of the cam sprocket which there is plenty of anyway.

|

| 04:57 |

Essentially, this small change can save a few hundred dollars in material costs.

|

| 05:02 |

The next change was around tool size, which is something we can check to some degree with the minimum radius tool in Fusion 360.

|

| 05:10 |

The tight areas like the o ring groove and pockets for the breather baffle plate will require a small tool size regardless as the geometry in this area is critical to the functionality.

|

| 05:21 |

But they have been designed with relatively shallow cut depths to allow for this anyway.

|

| 05:26 |

The more demanding area is inside the valve cover where there are a lot of internal cavities and edges that will influence the minimum tool size.

|

| 05:35 |

The 5mm radius that was originally applied throughout would allow for a 10mm diameter tool which is available and suitable, however if this tool was used to machine vertical edges with machined radii and a significant depth like that of about 60 mm or so inside the valve cover, this can result in tool chatter, leading to a poor finish on these surfaces.

|

| 05:59 |

This can be addressed somewhat through different tooling and tool speed but reducing the depth of the cut would be more important in this case.

|

| 06:06 |

While we can't easily change the internal dimensions of the valve cover, increasing the radius of the fillets to 5.5 mm just 0.5 mm bigger than that of the tool, essentially achieves the same thing.

|

| 06:20 |

Removing the material removed and therefore preventing chatter.

|

| 06:24 |

A similar change would be required to the external vertical walls of the side of the valve cover which will be visible so we want the surface finish to be as good as possible.

|

| 06:34 |

Adding a 1° draught or angle to the outer walls so the walls slope outwards slightly towards the bottom of the valve cover, achieves the same result, reducing the cut depth and the material removed and preventing chatter.

|

| 06:48 |

An accessibility analysis can also be completed in Fusion 360 showing overhangs or pockets which due to the geometry of the valve cover aren't a concern.

|

| 06:58 |

The majority of the machining can be done with two main setups, the right way up and upside down, but we'll dive into this a bit more when it comes to manufacturing.

|

| 07:08 |

In summary, there are a range of tools we can use within Fusion 360 to analyse our model with regards to geometry, strength, weight and DFM considerations.

|

| 07:20 |

In this case, it's a fairly simple process as the function of the part is also relatively simple.

|

| 07:26 |

However, the most important step is really communication with the machinist to understand any changes that need to be made to the model to allow for the most efficient process and the best finished product.

|

| 07:39 |

Some changes were made to the model to reduce the material cost and prevent tool chatter for a better finish.

|